In November 2025, the journal “Scientific Data,” belonging to the publishing group “Nature,” published an article by scientists from the I.I. Schmalhausen Institute of Zoology of the NAS of Ukraine and the National Museum of Natural History of the NAS of Ukraine “A high-resolution 3D reconstructed skeleton of the extinct dwarf whale Cetotherium riabinini from Ukraine” (“Skeleton of the extinct dwarf whale Cetotherium riabinini from Ukraine: high-resolution three-dimensional reconstruction”). The press service of the NAS of Ukraine interviewed the co-authors of the article – scientists from the Department of Evolutionary Morphology of the I.I. Schmalhausen Institute of Zoology of the NAS of Ukraine: research fellow, PhD Svytozar Davydenko (the idea author and corresponding author of the article) and leading research fellow, Doctor of Biological Sciences, Professor Pavlo Holdin (author of the modern description of the skeleton of Cetotherium riabinini, Svytozar’s mentor).

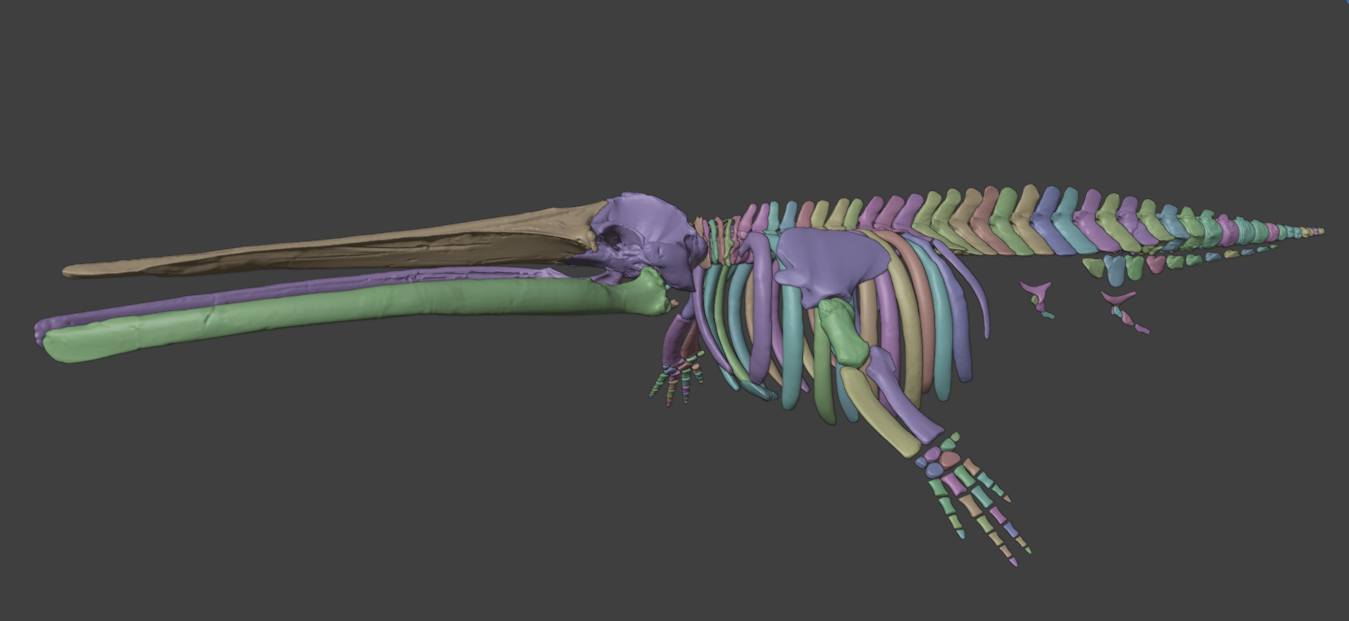

3D model of the skeleton of Cetotherium riabinini. Illustration from Svytozar Davydenko’s Facebook page

– Mr. Svytozar, how did your research with colleagues, described in the new article, begin? What makes it interesting?

– In 2021, even before the full-scale invasion, we acquired [thanks to a grant from the National Research Foundation of Ukraine] special equipment for scanning objects of various size categories – from small ones a few centimeters in size to, for example, complete skeletons of large whales – blue whales or similar. While mastering the equipment, we practiced scanning various objects. At that time, we first scanned the skeleton of Cetotherium. It is unique because it is probably one of the most complete specimens among all fossil whales: this skeleton has a skull, jaws, limb bones, almost the entire spine, ribs. Some elements are lost or broken, but overall its preservation is unique. There are very few such specimens in the world. In particular, no complete skeletons of whales from the family Cetotheriidae, which includes dwarf species of baleen whales, are known.

– Where are these remains stored? And where were they found?

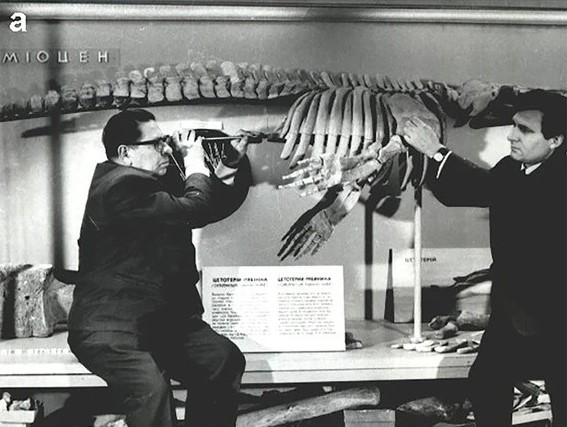

– Currently, the Cetotherium is stored at the National Museum of Natural History of the NAS of Ukraine. Back in the 1960s, it was taken out of storage and mounted for exhibition. It still stands there. The remains were found before World War II, in 1930, on the outskirts of Mykolaiv.

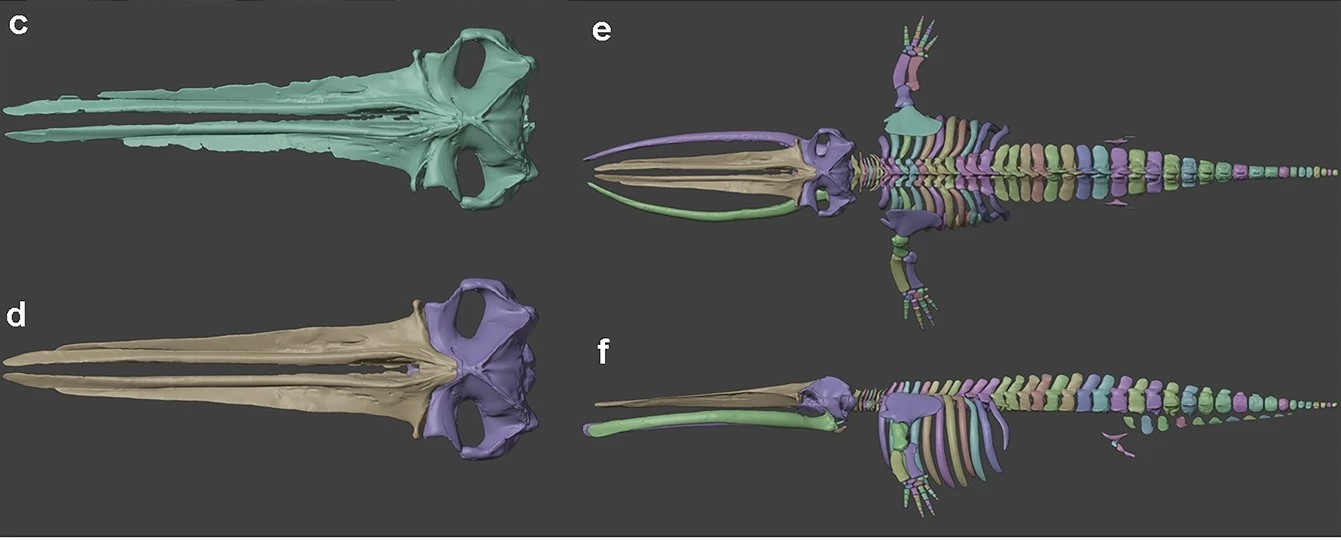

So, using special equipment, we digitized the Cetotherium skeleton, created its 3D model, and posted a simplified version on the Sketchfab website [Sketchfab is an online resource for storing content in 3D, virtual, and augmented reality formats], where many scientific institutions and museums place their virtual collections. Why simplified? Because the site has file size upload limits.

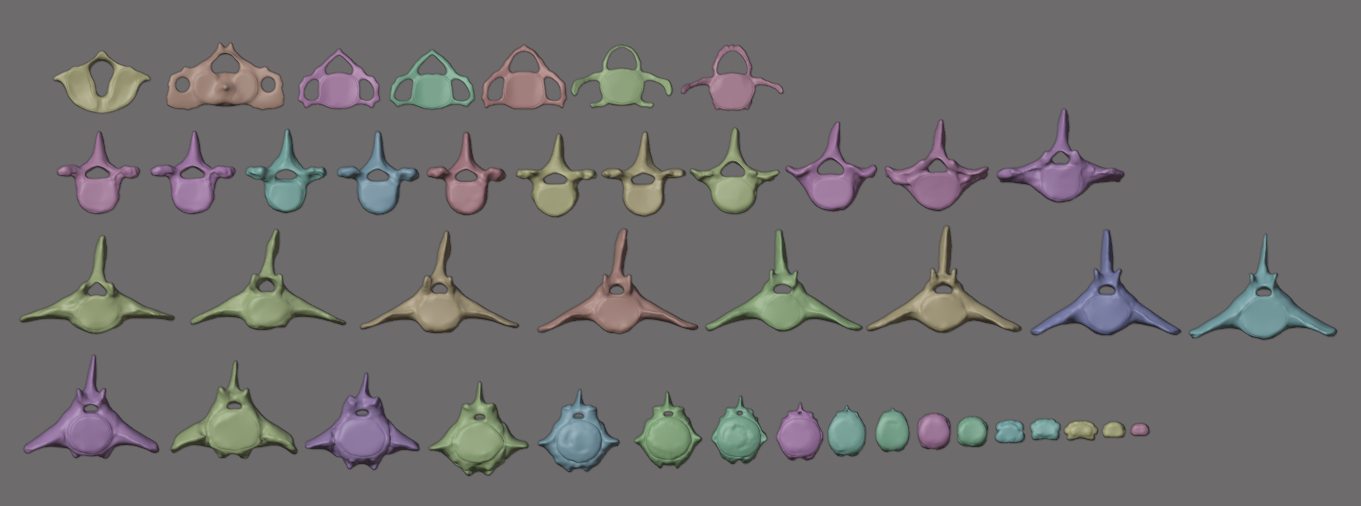

But our 3D scan is a single continuous three-dimensional model, a single structure, a monolithic piece. That is, the skeleton is not divided. Therefore, later I had the idea to visualize each vertebra and each bone separately. This can be done using a 3D editor. To recreate them, we made virtual cuts at the bone junctions, and modeled the areas of openings based on, for example, illustrations of skeletons of related species.

Then Pavlo Yevhenovych and I noticed something important. Before World War II, our Cetotherium was described by a researcher named Hofshtein, and in 2013 Pavlo Yevhenovych redescribed it in a modern context because many additional materials were found, which, among other things, allowed clarifying the phylogenetic relationships of this species. Based on this more recent publication and consultations with Pavlo Yevhenovych, we concluded that the skeleton was incorrectly assembled in some places: some vertebrae were swapped, some extra bones were present, and in other places, something was missing. Moreover, there is a set of separate bones stored in the Museum’s collections separately and not included in this mounted skeleton because they cannot be fitted – they would be floating in the air. But I decided it was worth scanning these additional bones as well. Then I cut all these elements into separate components and assembled them in anatomical order, as it should ideally be, according to modern understanding of the anatomy of these whales. We thought it would be good to present these new findings as a publication – together with the original scan of our model. As part of Ukrainian heritage. And fully share this with the scientific community.

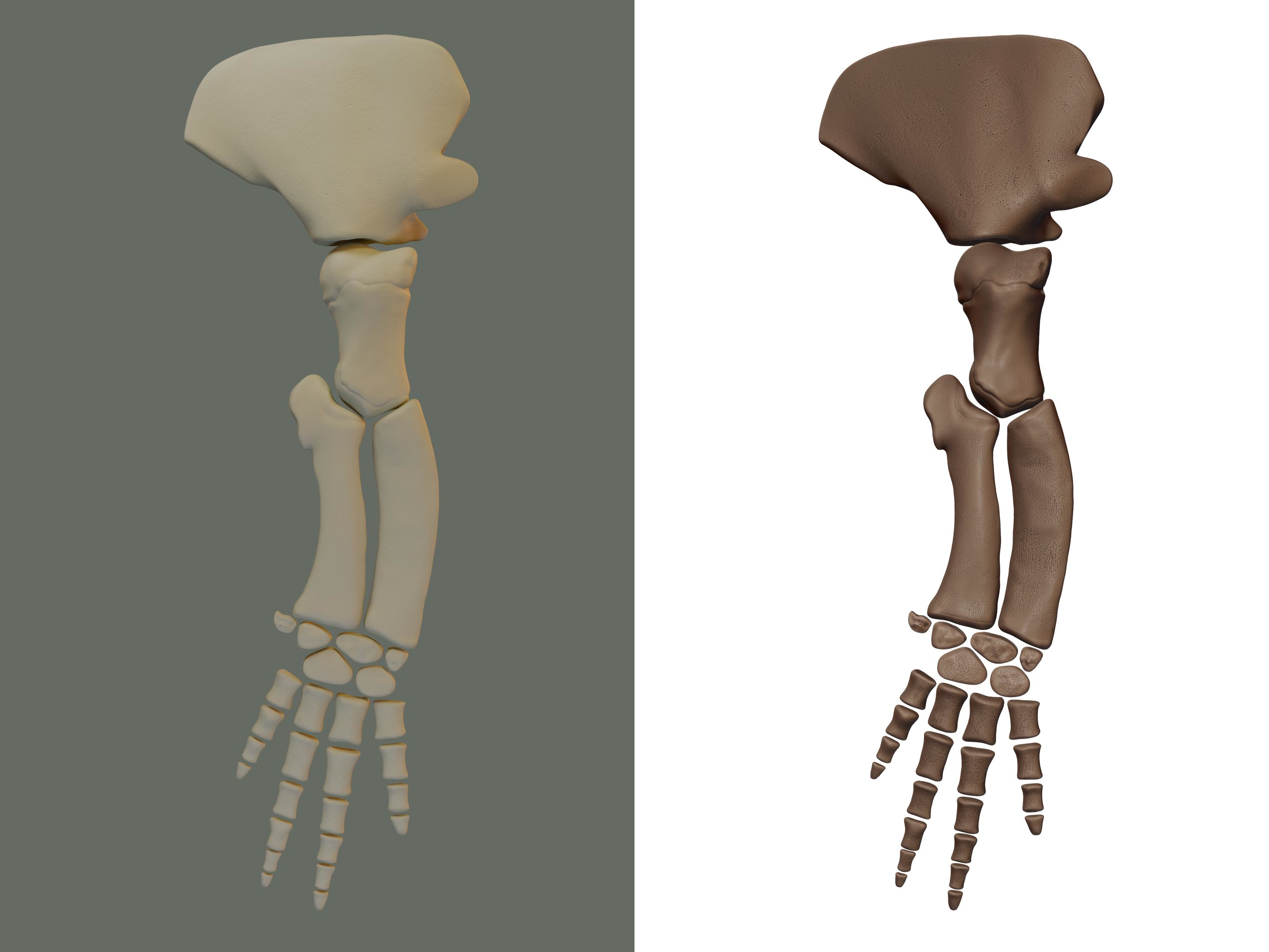

Virtual reconstruction of the forelimb (flipper) of Cetotherium riabinini

Separate models of cervical, thoracic, lumbar, and caudal vertebrae of Cetotherium with reconstructed articular surfaces (front view)

Scan of the skull before (c) and after (d) virtual restoration; virtual 3D reconstruction of the complete skeleton of Cetotherium riabinini (e, f). Illustration: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41597-025-06086-2

– What is the scientific value of your article with colleagues?

– First, it is useful for further biomechanical studies. Thanks to the reconstruction of individual bones, it will be much easier to reconstruct the muscle system of this whale and so on, to understand how it moved and what were the degrees of freedom of its spine. From a single solid structure, this is not clear, but individual elements can be rotated in certain anatomical positions to see how much the spine could bend in different planes. The same applies to the skull. Much has already been said about the cranial kinesis of baleen whales, but further research is still needed. Because whales are among the few mammals whose upper jaw is also partly movable (a similar convergence occurs in some birds). For virtual modeling of this mobility, our scan will also be useful. We published it in the very diverse journal “Scientific Data,” dedicated to scientific datasets: genomes, other data sets, photographs, and models are published there. Now our result is also available. And it is accessible to everyone.

– Do you plan to do something similar for other objects?

– We are currently planning to develop a method for digitizing skeletons of large whales – blue whales, fin whales, etc. Some of them are in the same Museum. For example, skeletons of fin whales and sperm whales. But this is a very specific task because they are mounted hanging from the ceiling or standing close to the wall, so scanners cannot simply approach them. Therefore, we are thinking about using a small drone for this. It will fly around the skeletons, photograph them, and based on these photos and photogrammetry, we will create a 3D model. Something similar has already been done in science, but only once so far: Italian researchers successfully digitized a mammoth skeleton this way.

– What do you do besides whales? I heard you are about to head to the South Pole again soon. [The conversation took place on November 21, and on November 24 Svytozar Davydenko went on an expedition.]

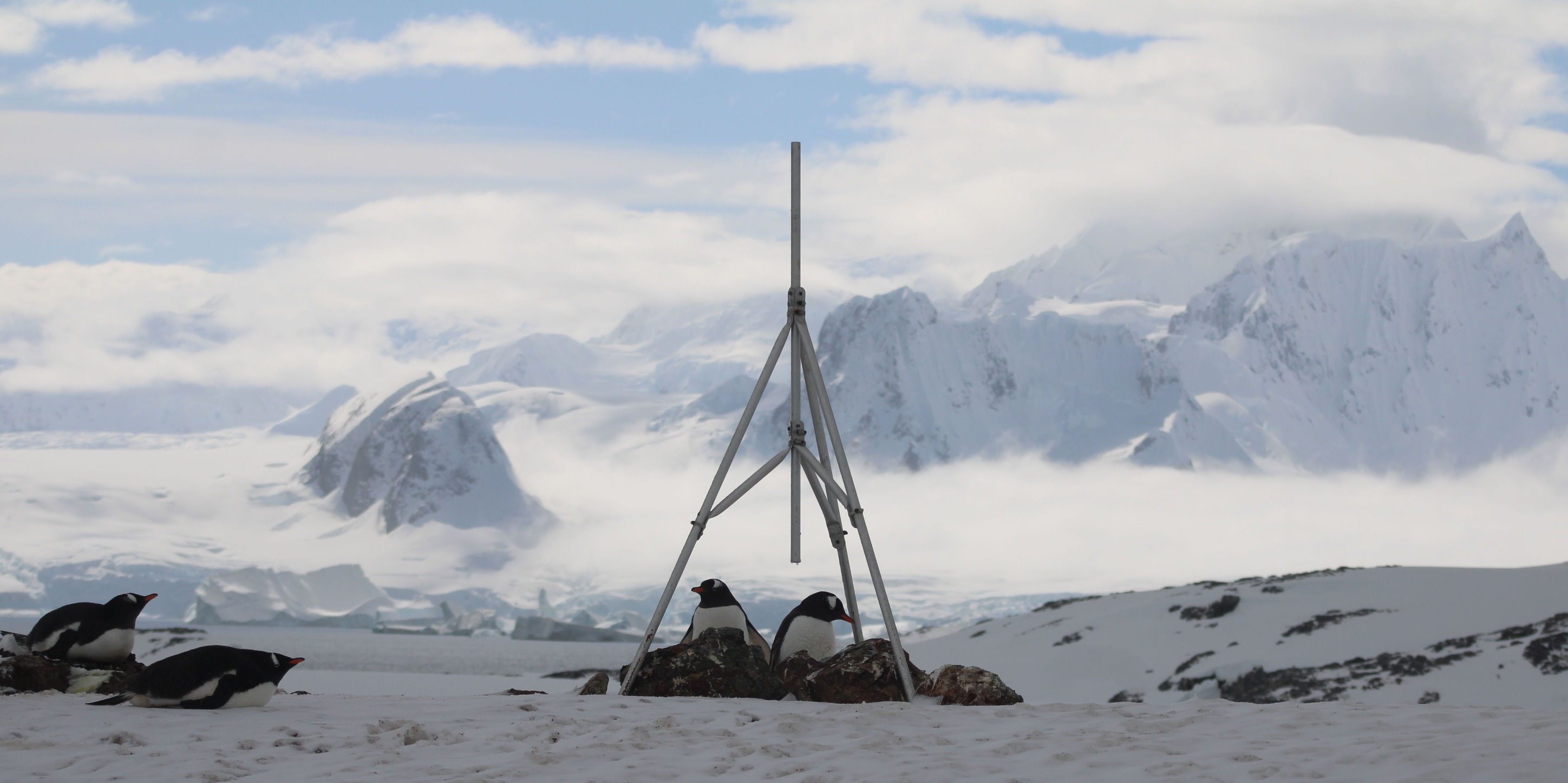

– First, a few words about whales. I mainly study their evolution, morphology, paleontology. In general – the body structure of whales, primarily bones, but also everything related to them. For example, based on the skeleton, I reconstruct muscles and overall body size. This gives a better understanding of the ecology and lifestyle of fossil forms. I also study penguins at the Ukrainian Antarctic station “Akademik Vernadsky.” I am the curator of the CEMP program – CCAMLR Ecosystem Monitoring Program (CCAMLR – Commission for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources) [Krill consumption monitoring program].

Face of a humpback whale. Photo from Svytozar Davydenko’s Facebook page

Subantarctic penguin with chicks near the Ukrainian Antarctic station “Akademik Vernadsky.” Photo from Svytozar Davydenko’s Facebook page

Subantarctic penguins during the breeding season (Galindez Island, Antarctica)

– Is this an international project?

– Yes. It is dedicated to monitoring species that feed on krill: penguins, whales, seals of various species. Several penguin colonies live at the “Akademik Vernadsky” station and surrounding islands. We monitor them annually and submit reports on their status to the CCAMLR secretariat. There are many such monitoring points like our station. They also provide data based on which the krill fishery is regulated – the program secretariat makes decisions regarding krill harvesting permits.

Now I am preparing for a short seasonal expedition on the Ukrainian ship “Noosphere.” I will be collecting plankton from various points along our route. These data will then be analyzed by professional plankton experts.

Svytozar Davydenko during the 29th Ukrainian Antarctic Expedition (2024–2025). Photo from Svytozar Davydenko’s Facebook page

Joining the conversation is Svytozar Davydenko’s mentor and co-author of the article – Doctor of Biological Sciences, Professor Pavlo Holdin.

– I want to briefly explain what exactly we are dealing with, what kind of whale this is, and why it is so unique.

First, the whale whose skeleton we digitized is a Cetotherium (more precisely – Cetotherium riabinini), a representative of the smallest baleen whales in Earth’s history, cetotheriids, which were comparable in size to dolphins: their body length was only 3 meters. This is very small, corresponding to the length of modern Black Sea bottlenose dolphins. Currently, no living whales of this size exist on Earth. The smallest modern whales – dwarf minke whales, which are apparently somewhat close relatives of cetotheriids and live in the Southern Hemisphere – have a length of at least 6 meters (in adults). So 3 meters in length today can only be newborn calves. Therefore, digitizing the skeleton, which opens the way to reconstructing the body and appearance of our Cetotherium (which Mr. Svytozar is currently doing), provides a starting point for all the smallest whales that no longer exist. Thanks to this skeleton, we can imagine what the smallest whales in the history of our planet looked like. This is very important because there are no other such complete cetotheriid skeletons anywhere except Ukraine. About 20 species have been described in this family, but none of their representatives have been preserved as completely as our Cetotherium riabinini. Comparable-sized whales can be found in South America (Peru) and North America (California), from the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. But all of them are represented by fragments: either a skull (at best – complete) or some bones from the spine or limbs. But none of them have such a degree of skeleton preservation as Cetotherium riabinini. So this is the only skeleton in the world from which such a whale can be reconstructed. And that is its enormous scientific significance.

Second, its belonging to our cultural heritage is important. Since this is the most complete cetotheriid skeleton in the world, it is basically our national brand. Thanks to this fossil, Ukraine is known or can be known worldwide. The USA, for example, has tyrannosaurs; Australia – the oldest Cambrian organism imprints; Canada – the Burgess Shale; Myanmar and Brazil – ambers. And what is unique about us? What do we have that we could present to the world? Certainly, Ukraine also has its amber. But if we talk about vertebrate animals, it is the skeleton of Cetotherium riabinini.

Third, it matters that cetotheriids were described specifically from the Black Sea. And the very first of them is one of the first described fossil whales: Cetotherium ratkei, found on the shore of the Kerch Strait. It was kept in Kerch but is now taken to Moscow. Among whales of the genus Cetotherium, only two skulls are known: one is this Cetotherium ratkei, now in Moscow, and the other is the Cetotherium riabinini found in Mykolaiv, now in Kyiv. These whales are very rare (and their skulls even rarer), and they were first described 200 years ago based on finds from the Black Sea region.

Fourth, this skeleton has a very dramatic history of discovery and study. The whale was found in 1930 on the then outskirts of Mykolaiv (now part of the city). It was excavated, carefully assembled, and brought to Kyiv. The skeleton was studied by the famous Ukrainian geologist and paleontologist – then still very young, practically a student – Illya Davidovich Hofshtein. His life was long but tragic. He prepared a description of this whale, then went to war, and when he returned, the papers were lost. There is no archive or specific description. Hofshtein understood that it would take a long time to restore the information. So he first published a very short article, almost a note, indicating that he found and described a new whale species and would later restore the description. That is, he recorded the fact of discovering a new species in scientific literature. In the 1950s, Illya Davidovich’s father – the famous Jewish poet and writer David Hofshtein – was repressed and executed. The son was sent into exile, after which he never returned to work at the Museum. When the charges against him were lifted, he moved to the Lviv region, where he became a specialist in oil geology, conducted explorations, and had students. As a scientist, he is known for these studies in Western Ukraine. He never returned to vertebrate paleontology. Thus, the whale remained practically undescribed – only named.

The skeleton of Cetotherium riabinini being mounted for exhibition at the National Museum of Natural History of the NAS of Ukraine. Photo from the Museum archive. Source: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41597-025-06086-2

The Museum was reconstructed, renovated, and a new exhibition was created where our Cetotherium was installed in 1966 or 1967. It stood there for over 40 years. Millions of Kyiv residents and visitors, schoolchildren, students, and tourists looked at it year after year, not realizing that for science it practically did not exist – there was only a name with nothing behind it. I first saw this skeleton in 2010 and realized that it was an unknown creature to science. So later I redescribed it and published the redescription.

Now we are undertaking the second stage of its study – at a new level: this is no longer just a redescription with photos but a high-quality 3D model. On the one hand, it will allow creating scientific reconstructions of this whale in multidimensional space. On the other hand, we at least partially preserve this three-dimensional image as a monument of our heritage. We will soon publish new results of our work. Stay tuned (smiles), follow the next articles by Mr. Svytozar and his good co-authors.

Preliminary results of 3D modeling of the external appearance of Cetotherium riabinini. Illustration from Svytozar Davydenko’s Facebook page

Interviewed by Snizhana Mazurenko