On October 14, 2024, the next laureates of the Sveriges Riksbank Prize in Economic Sciences in Memory of Alfred Nobel (also known as the Nobel Prize in Economics) were announced: professors Daron Acemoglu and Simon Johnson from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (Cambridge, USA) and professor James Robinson from the University of Chicago (USA) were awarded “for research on how institutions are formed and affect prosperity.” The results honored by this prestigious award and the contribution of their authors to the development of economic science are discussed by the head of the Department of Economic History at the Institute of Economics and Forecasting of the NAS of Ukraine, Doctor of Economics Victoria Nebrat, in an exclusive article for our Academy’s website.

Source: www.nobelprize.org

For the second consecutive year, the Nobel Prize in Economics is awarded for historical-economic research. This recognizes not only the achievements of specific scientists (Claudia Goldin – in the field of labor market evolution and female employment in a long-term retrospective; Daron Acemoglu, James Robinson, and Simon Johnson – in revealing the importance of institutions for the welfare of nations), but also an entire branch of economic science that not only states the past and explains the present but is also capable of predicting the future. How else can one explain such interest in the history of power, wealth, and prosperity if not by the desire to grasp the secret of their achievement?

This year’s laureates do not impress with the originality of the problem’s formulation – the question of the nature and causes of the wealth of nations remains key in economic science since the time of Adam (Smith) and his famous 1776 work (original title – “An inquiry into the nature and causes of the wealth of nations”). What is more interesting is the authors’ approach to solving this classic question.

In their book “Why Nations Fail,” Daron Acemoglu and James Robinson demonstrated on a vast historical material that natural resources and a generous climate, favorable geographical location, and the industriousness of inhabitants cannot protect a country from impoverishment and decline. Conversely, resource-poor territories demonstrate “economic miracles.” By comparing the current level of development and even the everyday life of residents of neighboring countries, the authors intrigue with the question: what is the reason for such differences?

The answer: the quality of institutions. But this answer is as true as it is too general to clarify anything. Moreover, economists’ appeal to institutional analysis also has its history. Douglas North and Robert Fogel also pointed to the nature of institutions and the mechanism of institutional change as decisive factors in the functioning of economies [1]. They argued that the present and future are connected with the past by the continuity of social institutions – regulators of economic interaction among people. By the way, they were also awarded the Nobel Prize (in 1993) for this.

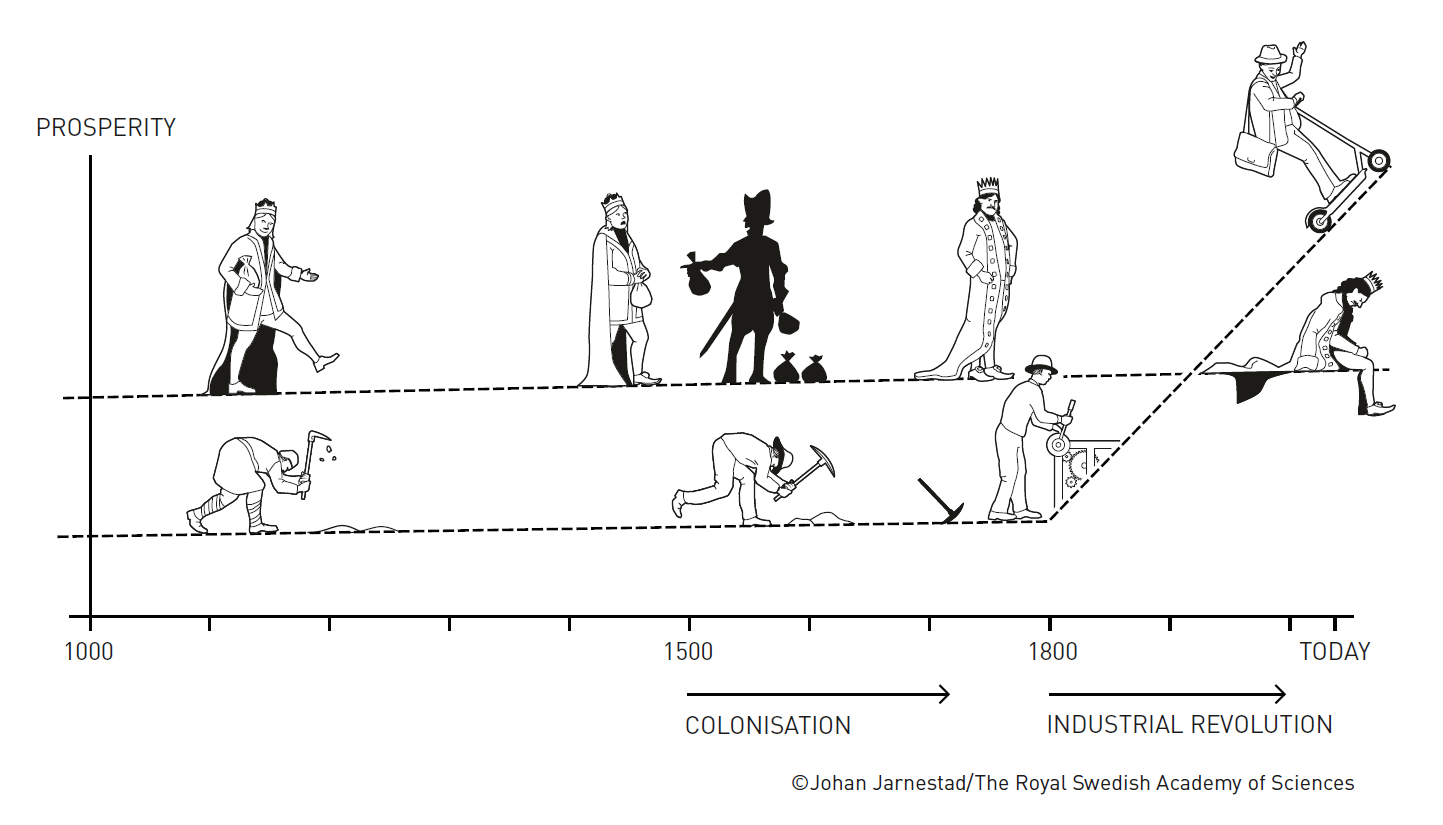

The novelty of this year’s laureates’ research lies primarily in revealing the interaction of political and economic constraints and incentives. When the political elite builds a system of resource and income extraction in its clan interests – neither development nor welfare for the country and nation is possible. Power aimed at restriction and coercion builds an economic model in which human and economic potential are exhausted but do not ensure long-term endogenous growth. There are no internal intentions for development and improvement, thrift and innovation, optimization, and creativity in management.

To some extent, the combination and disclosure by the laureate scientists of the synergy of political and economic institutions in their determination of wealth and welfare (or poverty and decline) is an argument in favor of the rehabilitation and revival of political economy as the science of the interaction of politics (regulatory norms established by state power) and economics (forms of organization and efficiency of the social economy). After all, corruption in government and its inability to provide quality management services (which the authors consider using examples from Egypt, Congo, Ethiopia, and many other countries) lead to inequality of economic opportunities in people’s realization of their abilities. This, in turn, not only reduces the country’s production and innovation potential but also pushes out the most active and productive part of the population in search of better conditions for self-realization, adequate income, and quality of life.

Power monopolized by a narrow circle of elites organizes society for its own benefit at the expense of others, that is, it forms extractive political and economic institutions. The authors define their essence as follows: “Extractive institutions are created to take income and benefits from one social group for the benefit of another” [2, p. 70]. This year’s laureates demonstrated this on a vast historical material – from the conquest and colonization of South America to modern North Korea and Zimbabwe. The distribution of political rights (as in the USA and the UK), the certainty and observance of laws, government accountability to citizens open opportunities for broad participation in economic life for their benefit. This, in turn, sets the dynamism of technological development that ensures leadership. Thus, political and economic institutions create both incentives and constraints. Depending on which function dominates, society moves toward prosperity or decline.

Another question that concerns Ukrainians: why do revolutions sometimes fail to bring the desired changes? If power is ineffective, why does its change not improve the situation? The answer also has a historical basis. Daron Acemoglu and James Robinson argue: the important thing is not the change of power, but the change of rules. In a hierarchical society where power and wealth are concentrated in the hands of a few, constant struggle accompanied by economic losses and human casualties is inevitable. Poverty and tyranny always go hand in hand. When groups fight for power to access resources and income in a poor society, there are high risks of establishing authoritarian regimes and sliding into dictatorship.

The quality of changes depends on the previous path, the scholars emphasize. For example, in the USA, a series of land acts and the 1862 agrarian reform opened space for market development and entrepreneurship, accelerating economic dynamics. In contrast, the 1861 peasant reform in the Russian Empire created new forms of peasant dependence and supported an economically passive and unproductive class of landowners. That is, differences in the previous development trajectory and dependence on it determine the further institutional divergence of countries – divergence in the transformation of institutional structures. This, in turn, exacerbates global inequality. The model of extraction of the poor and underdeveloped by the wealthy and efficient is repeated at the global level.

At the same time, as the authors of the global bestseller state, “every society functions within a set of economic and political rules formulated and effectively supported by both the state and citizens. The political process determines under which economic institutions people will live, and it is the political institutions that outline how this process will occur” [2, p. 41]. Although economic institutions are critical for nations’ movement toward wealth or poverty, it is politics and political institutions that determine what these economic institutions will be. Inclusive economic institutions encourage economic activity, stimulate productivity growth, and promote economic welfare. They create inclusive markets, ensure a competitive environment, pave the way for drivers of prosperity such as technology and education, and generate demand for scientific research and entrepreneurial innovation.

“Nations fail when they have extractive economic institutions supported by extractive political institutions, resulting in economic growth being constrained or even blocked” [2, p. 76]. Daron Acemoglu and James Robinson explain that “poor countries suffer because of the choices of the powerful, which create poverty. They act wrongly not because of mistakes or ignorance, but deliberately” [2, p. 62].

The key question remains: how can political elites be uninterested in economic growth? Why do the powerful block progressive changes, restraining the development and rooting of inclusive institutions that would ensure prosperity? The answer lies in the risks and threats that accompany progress. After all, economic growth creates new winners and losers, redistributes power and money. Creative destruction, as Joseph Schumpeter called this phenomenon, changes social roles and undermines the authority of yesterday’s leaders. This was the case with the landed aristocracy during the Industrial Revolution when the development of machine production and wage labor first reduced the income and then the power of landowners. In the Russian and Austro-Hungarian empires, absolute monarchy and the landed aristocracy consolidated to block industrialization. As a result, the economies of these states began to decline, and social tension increased. In the article “Political Losers as a Barrier to Economic Development” (2000), Daron Acemoglu and James Robinson formulate this explanation as follows: “Existing powerful interest groups block the introduction of new technologies to protect their economic rents, and societies can achieve technical progress only if they can overcome such groups” [3, p. 127].

Source: www.nobelprize.org

The lesson from the historical experience of many countries trapped in poverty and backwardness, dependent on others who are more successful, is formulated simply by scholars researching the causes of nations’ decline: “Development occurs only when it is not blocked by economic losers who feel their economic privileges will be lost and political losers who fear losing their political power” [2, p. 78]. The conflict of interests over limited resources, income, and power turns into a conflict over the rules of the game – economic institutions. Institutional development trajectories of countries differ significantly, but changing one’s own trajectory, stepping beyond the historically trodden path, is equally difficult. At the same time, Daron Acemoglu, James Robinson, and Simon Johnson once again prove the impossibility of universal recipes for economic prosperity.

A feature of research on the history of institutions is its interdisciplinarity. Seeking answers to questions about overcoming barriers to economic development and social welfare, this year’s Nobel laureates in economics conducted a series of studies at the intersection of general history, economics, political science, cultural studies, legal history, and other fields of knowledge. Daron Acemoglu, co-authoring with James Robinson, wrote the books “Why Nations Fail: The Origins of Power, Prosperity, and Poverty,” “Economic Origins of Dictatorship and Democracy,” “The Narrow Corridor: States, Societies, and the Fate of Liberty.” Simon Johnson and Daron Acemoglu authored the book “Power and Progress: Our Thousand-Year Struggle Over Technology and Prosperity.” They are united not only by common themes but also by the methodology of institutional analysis and the focus on building human-centered societies and economies.

The main protagonists of change on the path to a democratic society with an effective economy are people who, in Daron Acemoglu’s words, “defend their own freedoms and actively establish limits on how rules and behaviors are imposed on them.” In the “narrow corridor” between the alternatives of lawlessness and authoritarianism, society and the state must achieve a balance of freedom and restrictions [4]. When social groups and the active part of society compete with state power and use it to help ordinary citizens, freedom expands. Consequently, opportunities for development based on inclusiveness and innovation grow. Thus, the question of the future cannot be left to the ruling elites because they may use state power to strengthen the system of extractive institutions, which in the long term are doomed but in the short term are destructive to the economy and society.

What determines the predictive potential of this year’s Nobel laureates’ ideas in economics? First of all, the fact that they pointed to current trends that shape future risks and challenges for individual countries and the global community as a whole. The development of technology as the basis of economic growth conflicts with the conditions for the development and self-realization of the individual. Artificial intelligence negatively affects not only employment and wages but also democracy. The system of supranational regulators limits the same development institutions that contributed to the formation of the modern global economy. The pursuit of freedom through the rejection of one’s past can lead both to tyranny and anarchy, since building a democratic system is not just about destroying the old institutional order.

The main challenges we face today, as Daron Acemoglu noted, are creating an appropriate political balance and mobilizing society without depriving laws and institutions of their powers. In the book “Power and Progress,” Daron Acemoglu and Simon Johnson justify political proposals to minimize the negative externalities of technical progress, including strengthening market incentives, breaking up large technology companies, tax reforms, investments in workers, and protection of privacy and data [5].

What is the special interest and value of the historical-economic studies awarded this year’s Nobel Prize for Ukraine? First, they explain our own history, although they consider the retrospective of institutional transformations from the Ancient World to the present on all continents. Second, on a broad material integrated by the overarching idea of the influence of institutions on economic welfare, Simon Johnson, Daron Acemoglu, and James Robinson show the real role of power, laws, and civil society in building and protecting statehood, which is today an imperative for the existence of the Ukrainian nation. Third, the authors of global bestsellers convince that nothing is predetermined and inevitable, but rather the will of individuals and the consolidation of society based on understanding the previous path and a shared vision of the future can become a guide to success and prosperity.

References

1. North D. Institutions, Institutional Change and Economic Performance / translated from English by I. Dziub. Kyiv: Osnovy, 2000. 198 p.

2. Acemoglu, Daron; Robinson, James. Why Nations Fail? The Origins of Power, Prosperity, and Poverty / translated from English by Oleksandr Dem’yanchuk. Kyiv: Nash Format, 2016. 440 p.

3. Acemoglu, Daron; James A. Robinson. Political Losers as a Barrier to Economic Development. American Economic Review, 2000. 90 (2): 126–130. DOI: 10.1257/aer.90.2.126

4. Acemoglu, Daron; Robinson, James. The Narrow Corridor: States, Societies, and the Fate of Liberty / translated from English by Hennadiy Shpak. Kyiv: Nash Format, 2020. 520 p.

5. Acemoglu, Daron; Johnson, Simon. Power and Progress: Our Thousand-Year Struggle Over Technology and Prosperity. New York: PublicAffairs, 2023. 560 p.

Information from the Institute of Economics and Forecasting of the NAS of Ukraine